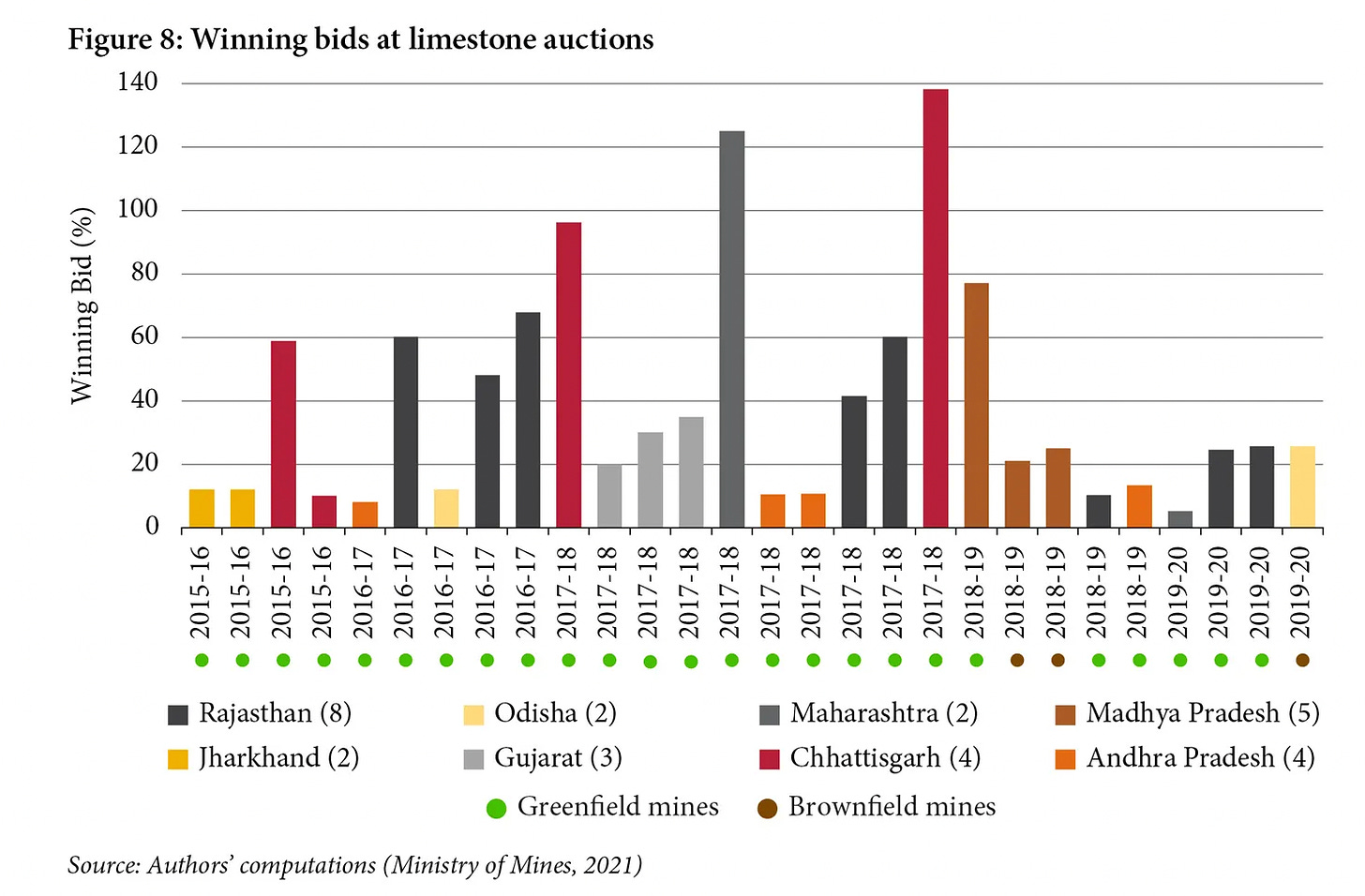

1 Auction premia and statutory payments exceed the minerals’ value

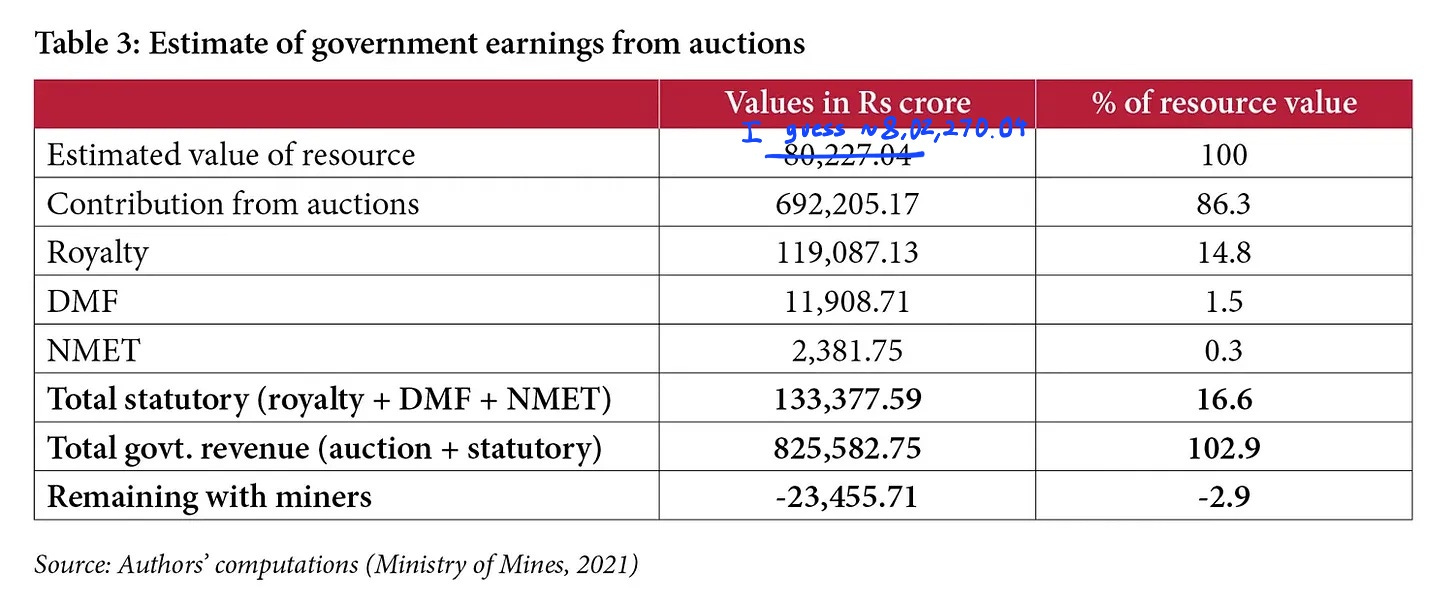

Rajesh Chadha and Ganesh Sivamani show, in their paper, how the payments that miners would make to the government for the privilege of getting the mining lease, namely auction premia, as bid by the miners themselves, and statutory payments, for auctions held from 2015-16 to April-June 2021-22 are more than the value of the resource estimated by the Ministry of Mines:

I’ve correct a typographical error

2 A brief primer on auction and statutory payments

The Ministry of Mines conducts electronic forward auctions amongst miners who they’ve “qualified.” They bid on the percentage of their sales based on the Average Selling Price (ASP), published on a monthly-basis by the Indian Bureau of Mines for that grade of ore (calculated as a weighted-average of the sale prices of merchant miners and open market sales of captive miners), that they’ll pay to the state government — this is called the auction premium. In addition to the auction premium, they have to make some statutory payments, which includes the royalty, contributions to the District Mineral Foundation (DMF) and the National Mineral Exploration Trust (NMET). The royalty is also paid to the state government, either as a percentage of their sales based on the ASP or some rupees on tonnage-basis, but they are defined in law unlike the auction premium which is the highest bid in the auction. Contribution to the DMF is 10% (for post-2015 auctioned mines) or 30% (pre-2015) of the royalty while for the NMET is 2% of the royalty.

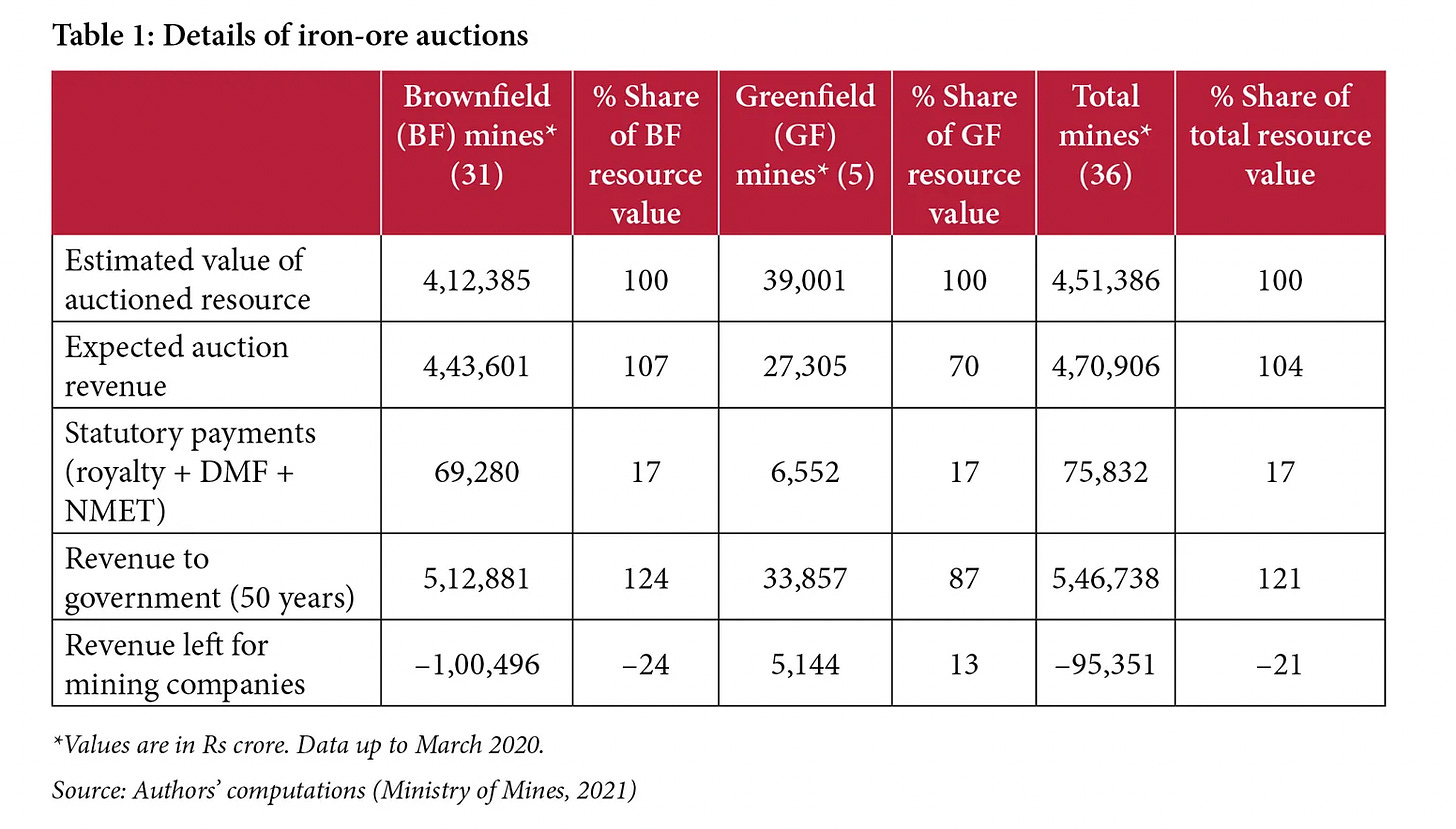

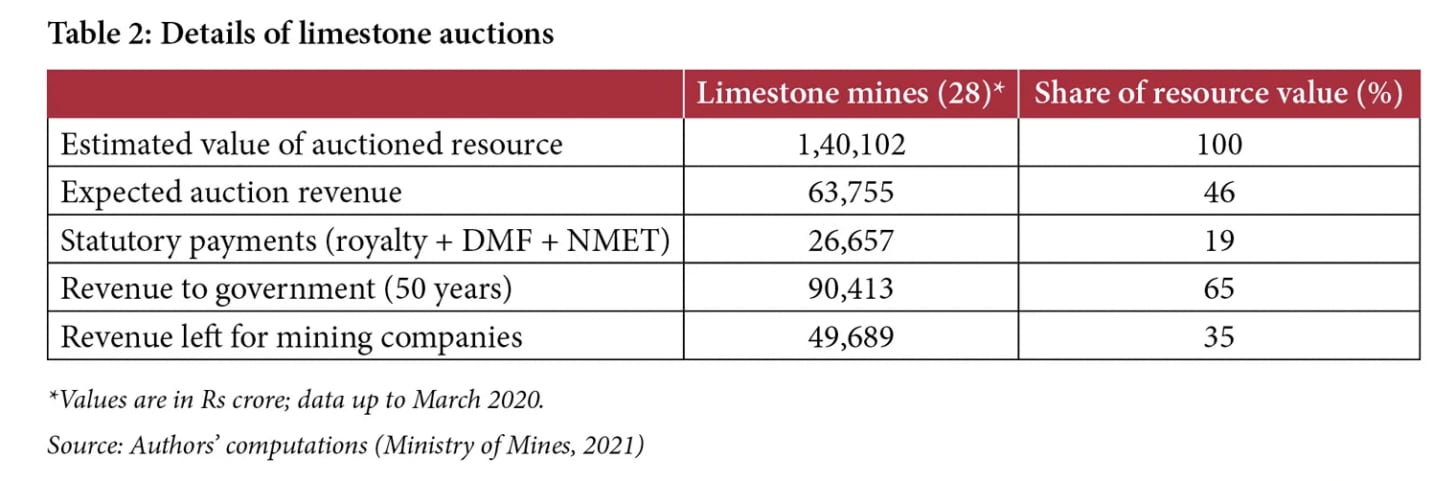

3 A mineral-wise breakdown

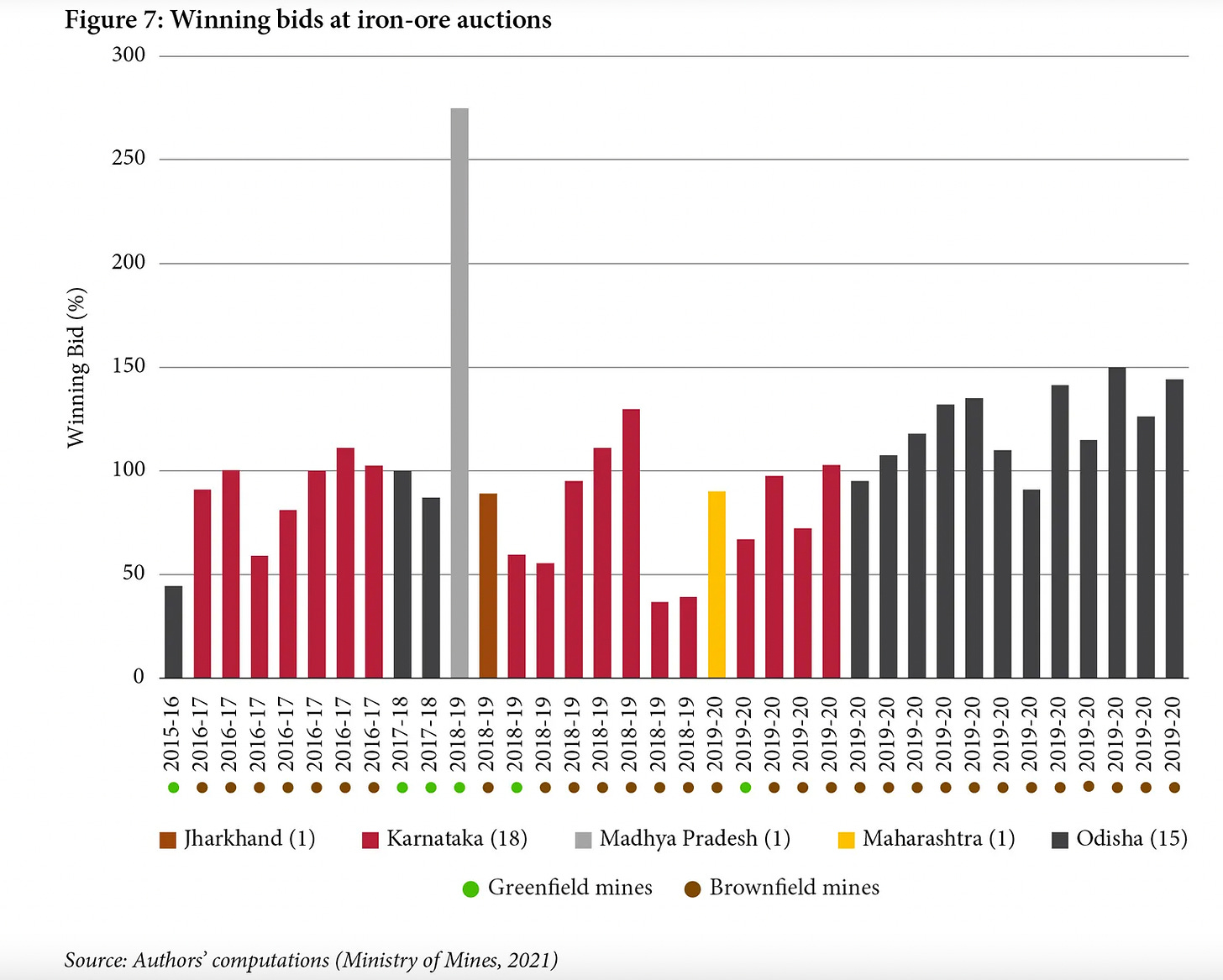

In some cases, I think very high (but less than 100%) auction and statutory payments may be rational for captive miners given the high rents in this industry — it’s just that their higher auction bids to secure the mine would have to be less than the higher price that they would have to pay to the merchant miner. But most of these payments combined were too high — more than 100% of the value of the mineral on a weighted-average basis!

4 How to make sense of the bids

I’m now going to list some of the answers to the obvious question, “Why are the bids so high — to the level of taking the auction and statutory payments more than the value of the resouce?” that I could find in the paper, from this presentation, from my conversations with Rahul Basu and my own premature understanding of the industry.

4.1 Absorb/not make a loss while following the law

The first reason that both the paper and corresponding presentation stress upon is that captive miners can absorb losses in their downstream businesses.

Most [reasons for overbidding] relate to the security of procuring raw materials. The cost of minerals may only be a small proportion of operations cost for downstream plants, but guaranteeing mineral supply would be important to the producers.

Given that the cost of iron ore for steel producers is only ~10-15% of the sale price of steel, the increase in price due to the higher auction and statutory payments might not be too much. If, for example, merchant miners mine iron ore at a cost of 50 and sell it at 100, including auction and statutory payments, while captive miners also mine at 50 but sell to their own steel plant at the same price (50) and then pay 100% of the 100 as auction and statutory payments, that totals 150 or 50 more than what merchant miners pay. Furthermore, if iron ore constitutes 10% of the steel’s sale price, then for captive miners, the increase is only 5% of the sale price of their final produce, which they can absorb, in exchange for a more reliable supply of perhaps their most crucial raw material.

They also stipulate that bidders expect policy changes in the future and just wanted to secure the mines till then.

4.2 Not make a loss while not following the law

In addition to these two legal ways, I think there are some ways that can actually make mining, even with obligations to pay auction and statutory payments of 100%+ of ASP, profitable but those ways are illegal. I’m not saying that they do engage in such activities or that they will, just that there are ways, that are illegal, that can be used to make their mining profitable.

One way in which such bids make sense is if miners under-report the grade of the ore that is mined and thus pay auction and statutory payments on a lower ASP, like what was recently a suspicion of the Ministry of Mines for manganese mined in Odisha. The price of grades vary drastically, so recording sale of a lower grade while selling a higher grade can be very profitable. For example,

The price of ore with less than 25% Manganese content is ₹3,228 while the same for ore containing Manganese content over 46 % is ₹20,407.

Second, miners can make up for the losses by keeping some produce totally off-the-books. This is not unprecedented. Off-the-book sales would not attract any auction premia or royalties and the potential higher profits could make the miner profitable overall. I think there’s no need for collecting payments in cash or through a non-banking channel — one can just setup a company that pretends to do, say “consulting,” and ask the buyer to also get into a contract to take the services of that consulting company (maybe through another company). They would then make the payment to that consulting company. As long as the real mineral reaches the buyer either without the administration’s knowledge or with their unofficial approval (which may or may not be in exchange for stone gray or magenta pieces of paper), everything should proceed smoothly.

Finally, there is a possibility of widespread under-invoicing of sales throughout the industry that is enough to underestimate the ASP. If the ASP is itself lower than what the actual sale price is for the same ore, mining can be profitable even with auction and statutory payments of 100%+ of ASP.